A Conversation With Biologist Dr. Andy Loveridge 10 Years After Cecil the Lion Was Killed

By Safina Center Environmental Journalism Fellow Marlowe Starling

Cecil the lion at 11 years old in Hwange National Park. ©Paul Funston/Panthera

Cecil the lion was 13 years old when American dentist Walter Palmer shot him with a bow and arrow just outside of Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe.

Palmer had the permits he needed to carry out the recreational activity known as trophy hunting: Killing megafauna with particularly impressive traits for the sake of taking a photo or displaying the animal. But Cecil, who had been tracked with a GPS collar for eight years by then, had become somewhat of a celebrity. When he was killed, the media exploded into a frenzy.

The incident garnered attention to what was already a heated debate over the ethics and conservation value of trophy hunting in Africa. Though deemed cruel by some, others would argue trophy hunting is somewhat of a necessary conservation tool in wildlife-dense African countries, many of which lack adequate funding for wildlife protection. The revenue trophy hunting generates can support conservation, but it can also damage the genetic strength of populations containing individuals with sought-after features: a long horn, a lush mane, or a regal pelt.

Now, a decade later, trophy hunting is much more regulated, and lion conservation has come a long way. Indeed, Cecil’s death prompted regulatory changes to trophy hunting in Zimbabwe, which in turn bolstered the population.

Although the incident sparked outrage, it also spurred action. I spoke with Dr. Andrew Loveridge, director of Panthera’s lion program, about how Cecil’s death left an imprint on the conservation community.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

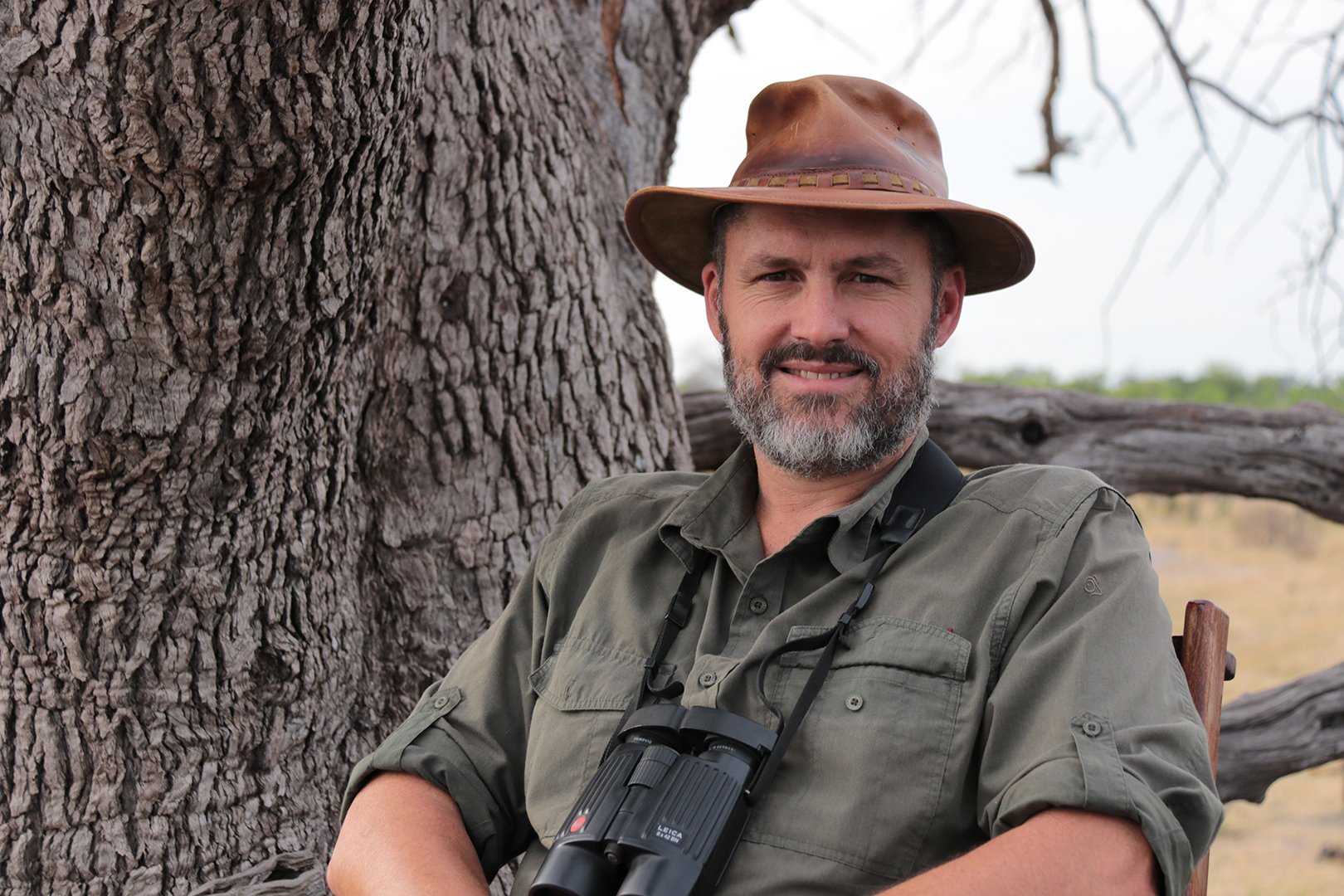

Dr. Andy Loveridge. ©Andy Loveridge

What did Cecil teach scientists about the role of GPS tracking in conservation biology?

When I first started studying lions 25 years ago, we didn't have GPS / satellite collars. That was a sort of emerging technology. Before that, we used to use a standard radio collar, which sends out a radio signal, and you've got to go and find the lion. What we found is that we could find the lion sometimes, but a lot of the time, we just couldn't find them, no matter how hard we looked. We even bought a small airplane, and then we could find them. But these animals are just moving over huge distances. So when we started putting satellite collars on them, we realized just how far they go.

The implication of that is you've got to have these absolutely huge landscapes to protect them. We kind of knew that, but we just didn’t know the extent to which they moved, and the extent to which they move outside and between protected areas, as well. Those things are really important to understand. You just can't get that information any other way than putting on a satellite tag.

Population monitoring is really important, and we do a lot of that at Panthera. We’re doing a lot of population surveys—lions aren’t that easy to count, surprisingly—and making sure that populations are stable or increasing, hopefully, in the areas where we work.

Cecil was obviously one of the animals we chose to put a tag on to get that kind of information to understand how they're behaving in the population, but also how they're moving within the landscape, moving outside the protected areas, coming into conflict with people, that kind of thing.

He was a very interesting lion in that when we first studied him in 2008, he was with a lion that we assumed was his brother, and when his brother was killed by the other lions, that caused Cecil to be displaced. We could follow his movements as he moved into another territory, lived with another pride, lost that pride, and eventually came back to his original territory. So, that's a real intricacy of lion behavior that was a kind of a consequence of having these collars to monitor those very detailed movements.

Cecil and a female lion at Hwange National Park. ©Paul Funston/Panthera

What were some of the immediate and lasting effects of Cecil’s death?

There was a huge media outcry and there was a huge amount of public attention, both focused on Cecil, but also focused on the conservation of lions. I think people suddenly realized that lions are not that common in Africa, they're declining, and if we don't do something about it, we're going to lose most of them. That's probably been one of the real outcomes of this: There's a lot more attention on these small populations that are very likely to go extinct if we don't do something.

It has translated into support and into funding for the kind of projects that we do. All the work I'm doing with Panthera probably stems a lot from that early attention. And I think people were sort of aware that tigers were disappearing, and lions were in a similar kind of decline. Public concern often translates into more political pressure, but it also mobilizes donors and supporters. It's allowed us to turn that concern into conservation action.

For context, what role does trophy hunting play in lion conservation?

In a lot of African countries, the country manages wildlife populations partially through trophy hunting, so they're not going to stop doing it. But they agreed to manage it more sustainably, which is exactly what should happen. More sustainable management, limiting trophy hunting to a very few individuals, made a big difference. Of course, hunting affects lions, because male lions are highly infanticidal, so as soon as they take over a new pride, they kill all the cubs. And so if you continuously trophy-hunt male lions, which is mostly what trophy hunters will hunt, they kill the cubs, and your population just doesn't grow or it declines. So it can have a really quite profound effect if it's not well managed.

Lioness and cubs at Hwange National Park. ©Panthera

How has lion conservation, and the conversation about trophy hunting, changed over the past decade since Cecil was killed?

I've been studying trophy hunting for a long time. When I first started working on it, it was almost completely unregulated. There were policies and regulations, but they weren’t the most appropriate. Since then, I think management authorities have looked at this much more closely and said, well, actually, we need to manage trophy hunting really well and scientifically. Universally, countries that trophy-hunt lions monitor it better and manage it better—if they don't, there could be a huge backlash.

Also, I think conservation action across Africa is much better than it was 10 years ago. The Lion Recovery Fund, for instance, was set up by the Wildlife Conservation Network after Cecil was killed. So that's putting millions (of dollars) into lion conservation.

Also, GPS technology has become a lot cheaper. Twenty years ago, it was very expensive. A lot of conservationists use it as a tool to monitor animals to make sure they're not getting into trouble. For one of the projects I'm involved in, we collar our animals that might come into conflict with people so that we can provide an early warning system to local communities and say, for example, ‘There's a lion out of the park, you need to look after your livestock, you need to bring your livestock in to protect it.”

Lions don’t like people. Quite often, these guys will get together a team of people, and they go and make a big noise using those plastic trumpets that football fans use in southern Africa. More often than not, the lion will just go straight back to the park. This also allows some of the people we work with to actually just chase the lion back into the park. That’s sort of a protective approach using this technology.

What other revelations has the scientific community had about lion conservation in the past decade?

You can't conserve lions without involving the local community. Particularly when the lions leave protected areas, they're going to come into conflict with people, kill people's livestock, and threaten people's lives. If we want to conserve these big predators and these ecosystems, we have to work with communities. We have to mitigate those conflicts, and make it worthwhile for people to live with lions as well.

Lion cubs at Hwange National Park. ©Paul Funston/Panthera

What’s next for the future of lion conservation efforts?

African governments just don't have the tax base to pay for conservation. They’ve got other priorities—health and education for instance—so conservation is quite far on the list. Paying for conservation is just critical. How do you do that? We haven't cracked that problem, but I think there are ways to increase the finances for protected areas. For instance, Panthera is doing a lot of park management support. We work with the park managers to improve training, to provide infrastructure and equipment, and it works.

A lot of our work has also been focused on monitoring lion populations, so we're getting some pretty good numbers on some of the areas where we work in Zambia and Senegal. In some of the sites, like the one near Niokolo-Koba National Park in Senegal, we've seen the lion population triple in 10 years. There were 10 lions left—that population was going extinct—and there are now 30 lions there. And it's increasing. Supporting conservation management through the local authorities is just so effective.

A really exciting development is that there are quite a few places in Africa where lions have been completely extirpated from parks, and we’re trying to find ways to bring lions back to “rewild” those ecosystems, effectively. It’s sort of been done in southern Africa, but in western and Central Africa, it hasn't been done, and they've lost a lot of their lions. That's something we're definitely trying to crack.